The repair clause for visible spare parts that we already know in European design Law [1] is about to be introduced in French law through an amendment[ [2] (quite cavalier) inserted in the bill on mobility [3].

In its last state [4], the text plans to establish a new double exception to the design right and also to the copyright, an exception that could be called “exception of repair of visible parts or appearance”.

This exception would first apply to copyright, with a new article L. 122-5, 12° of the Intellectual Property Code to allow also in this field the reproduction, use and marketing of parts intended to restore the initial appearance of a motor vehicle or its trailer.

In the field of design law, the legislator proposes to complicate everything further and to go more progressively, by limiting initially (as of January 1, 2020) the same exception of repair, but only to the parts of glazing, optics and mirrors. For other visible parts (bodywork), it would be necessary to wait until January 1, 2021, and only the OEMs who manufactured the original part for the manufacturers (so-called original equipment manufacturers) will be able to benefit from it. Finally, to top it all off, the residual protection of visible parts that would not yet be covered by these (variable geometry) repair exceptions would be reduced from 25 years to 10 years, but the provision is so poorly drafted that it makes little sense [5].

What should we think of this new reform?

Why, first of all, provide for a gradual application over time in design law and not in copyright law and why, therefore, limit the scope of the exception in design law, but not in copyright law?

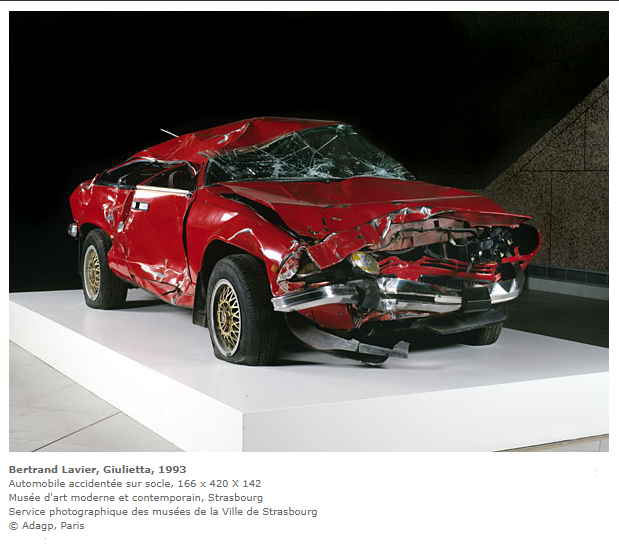

Certainly, a serious problem exists for these so-called “captive” parts in the sense that the lack of any competition on the repair market (due to exclusive rights) while the consumer no longer has any alternative, has allowed a constant rise in prices that is less and less bearable (by consumers and their insurers).

Our system, which provided (along with a few other minorities) for the full exercise of intellectual property rights on these visible parts while denying this problem, could no longer be sustained.

Should we, on the other hand, deny or neutralize the exercise (some would say) of intellectual property rights, the specific purpose of which [6]

is nevertheless threatened in case of aftermarket or repair?

A much more reasonable solution was proposed a few years ago by an American parliamentarian [7]: it consists in finally reconciling these exclusive rights with the need to promote competition on this particular market of visible parts for repair by imposing on the holders of the rights to grant a compulsory license to anyone who asks for it, and it should even be accompanied by the obligation to grant FRAND royalties [8].

A compulsory license to repair in exchange for FRAND royalties would be so much more intelligent than this new double exception, which is too radical and as ill-conceived as it is incoherent!

Charles de HAAS,

Avocat (Paris Bar)

[1] According to article 110 of Regulation (EC) 6/2002.

[2] Amendment n° CD2794, itself accompanied by various sub-amendments to constitute together article 31 sexies (new) of the project.

[3] Draft law on the orientation of mobility (No. 1831).

[4] The procedure of adoption is well advanced, the text having to pass in Joint Committee (CMP) before a last shuttle.

[5] The text refers to spare parts that are not already affected by the exception, but the author of these lines does not see any (objectively).

[6] That is, according to the CJEU, the reward by the granting of the exclusive right to manufacture and put into circulation any reproduction of protected objects in design law (CJEC, 5 Oct. 1988, aff. C 53/87 and CJEU, 26 Sept. 2000, aff. C-23/29) and the protection of the moral and economic interests of the authors in copyright law (CJEC, 20 Oct. 1993, RTDE, 1995, p. 845, obs. G. Bonet).

[7] For a presentation of this solution proposed by the Honourable Darell E. Issa, see our column in Prop. Intell. 2010, n° 37, p. 1029.

[8] For, if the setting of royalties is not, at a minimum, regulated, it will be sufficient for the holder to demand unreasonably high royalties to render the obligation to grant licenses meaningless. On the modalities of setting such a FRAND royalty, see Matthieu Dhenne, Petit précis de redevance FRAND à l’usage du vaste monde in Les inventions mises en œuvre par ordinateur : enjeux, pratiques et perspectives, Collection du CEIPI, n° 67, LexisNexis, 2019, pp. 173 et seq.