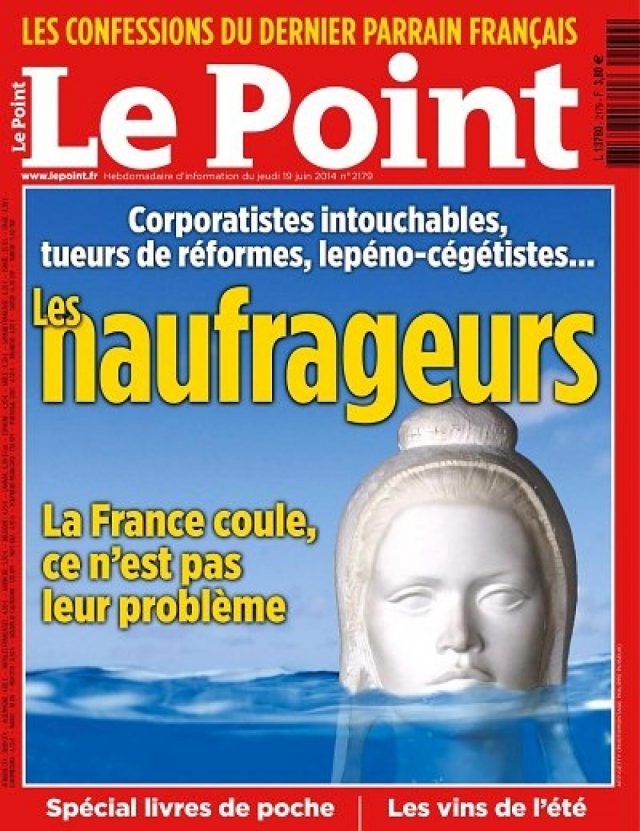

In a photomontage published on the front page, the magazine Le Point had reproduced the sculpture of the bust of Marianne made by the artist Alain Aslan, with the features of Brigitte Bardot, sinking under the waters with the title “les naufrageurs” and the subtitle “Corporatistes, intouchables, tueurs de réformes, lepéno-cégétistes…. (…) France is sinking and it is not their problem”. Summoned for infringement by the widow of the artist, the press organization, which had not sought prior authorization, invoked the exception of parody as a defense. With success.

According to the article L. 122-5 4° of the Code of the intellectual property “when the work was revealed, the author cannot prohibit: (…) 4° The parody, the pastiche and the caricature, taking into account the laws of the kind”. The conditions of application of this exception to the author’s economic rights are quite flexible. Despite these imprecise contours, the legal standard of the “laws of the genre” is nevertheless known and circumscribed. Two conditions define the main lines: (i) absence of harmful intent and (ii) absence of risk of confusion between the two works. These two conditions are recalled by the Court of Cassation in the decision under comment. But if the decision is worth noting, it is because it goes further.

By its decision of May 22, 2019, the Court of Cassation adds that the exception of parody escapes the moral prerogatives of the author of the parodied work in that it is not necessary to mention the source. To be fair, the solution is not new, but it is set out unambiguously by the Court of Cassation, which placed itself under the aegis of the CJEU’s case law by stating that it had “said as a matter of law”, in its judgment of 3 September 2014, that parody “is an autonomous concept of Union law and is not subject to conditions according to which the parody should mention the source of the parodied work or relate to the original work itself” (CJEU, 3 September 2014, aff. C-201/13 Johan Deckmyn and Vrijheidsfonds v. Helena Vandersteen).

One of the other interests of the commented judgment is that it is a reminder that copyright is evolving under the impetus of the European Union’s regulations, but also of the jurisprudence of the CJEU since national legislations are interpreted in the light of the directives (in this case, the Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonization of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society, which notably provides for the exception of parody, even though this exception existed in French law well before the European Union text).

This reminder is not insignificant at a time when the transposition into French law of directives adopted in the context of the Digital Single Market is underway, in particular the directive on copyright (directive on copyright and related rights in the digital market and amending directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC) and the directive on audiovisual media services (directive (EU) 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the Council of November 14, 2018 amending directive 2010/13/EU on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services, taking into account changes in market realities), regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services, taking into account the evolution of market realities).

We will have the opportunity to talk about this again.

Xavier PRÈS

Avocat (Paris Bar)